Ashoka University must stand by Ali Khan

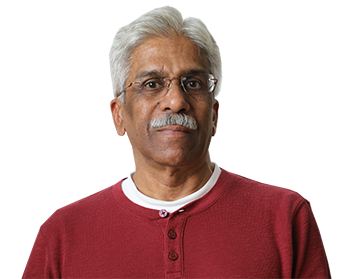

The arrest of Ali Khan Mahmudabad by the Haryana Police based on a law book of colonial provenance, its sanskritised nomenclature notwithstanding, has taken India to a particularly new low. Ali has been arrested for a series of social media posts in which he has praised the choice of women to explain Operation Sindhoor to the country, implying that it represents a recognition of gender and India’s religious diversity. He also called out the role of the Pakistani state in abetting cross-border terrorism that has killed innocent Indians for long. Ali then went on to engage a section of his countrymen asking them to address the issue of mob lynching and the state’s use of bulldozers as a form of justice. It is difficult to conceive of anything more patriotic. In fact, he has done seva to his country. Ali’s arrest has drawn attention to Ashoka University which he adorns with his international education, a family history of being in the public life of this country for over three generations and above all dedication to educating the young. His rectitude is reflected in the restraint in his response to charges made against him by the Women’s Commission of Haryana. It is as strong in their rejection as it is dignified. If I am asked to cite an instance of moral ambition shown by an individual in recent times it would be this.

Moral ambition, a term coined recently by the Dutch writer Rutger Bregman, is the passion for making the world a better place. By exhorting his country to aim at being a place where there is gender equality and religious pluralism he exudes such ambition. Leaving the world a better place is so transparently intuitive a goal that it stuns the imagination to find that it has not been shared by his university, Ashoka. In more than one statement made to media outlets it has distanced itself from Ali’s post, hailed the actions of India’s armed forces and clarified that it is cooperating with the authorities. The last is an egregious declaration, and whatever the university is signaling it is not moral ambition for sure. After all, it was clear why the authorities, first the Haryana Women’s Commission and then the police, were after him. Does Ashoka University consider what he did illegal? If it did not, it should have just left the law to take its course without the political signaling implicit in its statements that it wished to be seen as being on the right side of the Indian state. By proclaiming its willingness to cooperate it is implying that Ali has violated some section of the law or norm of accepted social conduct, which he has not.

As someone who productively spent close to a decade at Ashoka University, I observe its slide with some disappointment. It had a spectacular start in rapidly launching undergraduate instruction in the humanities and the social sciences to world class standards. It was able to recruit students from a wide range of backgrounds from the length and breadth of the country and then offer the most deserving among them substantial need-based financial aid. Faculty were given, and probably still are, full freedom to teach what they consider appropriate to their discipline. In fact, in this the administration showed itself to be more catholic than the faculty in some departments. However, all this pales besides the university leadership’s repeated response to pressure, whether actual or perceived it is difficult to tell, from the government and its agencies. Spread over close to a decade, in four instances that have reached the national press it has either caused the exit of its faculty or publicly distanced itself from the state’s clampdown on their freedom. In all instances, its faculty had shown itself to be critical of some aspect of the functioning of the government of the day. We do not have to agree with what they had said, and I do not in all cases, to see that they were engaged in the recognised business of a university professor and had violated no law of the land. Ironically, the very presence of the faculty involved in all these cases shows Ashoka as having succeeded in choosing persons with moral ambition, going beyond mere academic activity to engage with the world in a critical way, which is the very idea behind offering an education in the liberal arts. But the University showed itself without similar ambition when it failed to see their activity in the way that it did.

It is difficult to figure out exactly why Ashoka University acts in the way that it does. It cannot be that its worldly-wise leadership is unaware that clamping down on the freedom of expression does not earn it the admiration of its students. The young adore the rebellious. Or can it be that when it speaks of an education in the liberal arts it has in mind merely a transfer of the protocols and materials in use in American colleges without any commitment to freedom of expression? This can hardly be reassuring as many of them have recently caved in to Donald Trump’s ugly impositions. Perhaps the University should reflect on our past which shows India as a society in which through literature or in life there was glorification of those who spoke truth to power. From Mirabai to Kannagi, many of them were women and they all had moral ambition. If Ashoka has any, it will stand by young Ali Khan now.